It took me 40 years to climb aboard a sport bike so it’s no surprise that it’s 30 years old. That’s old for a motorcycle, but I’m 60, so it’s not old if you are me.

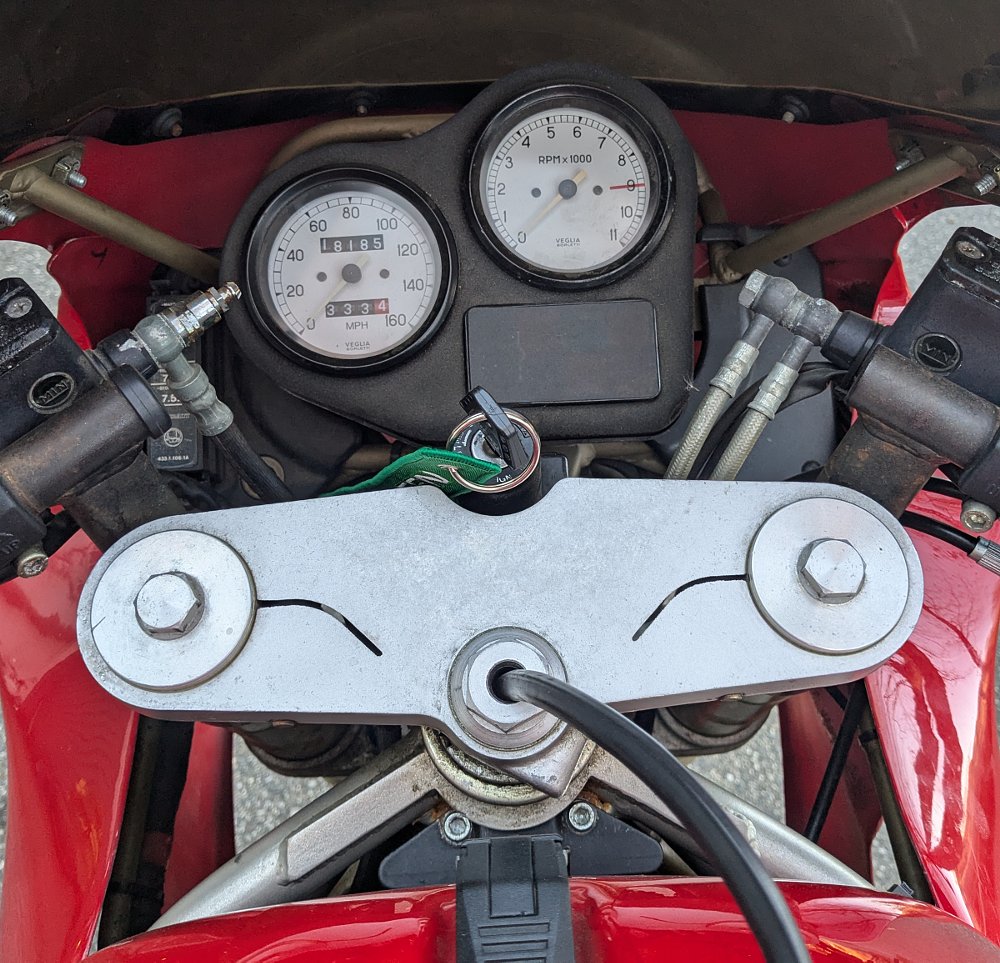

It’s a 1995 Ducati 900SS/CR, issued in the heart of the 1990s, a time when you could count on Ducatis to be V-twins with desmodromic valves and win the World Superbike championship. The 900 SS/SP was the higher spec version with a full fairing, adjustable suspension, and wider rear wheel. My SS/CR wears a half fairing, non-adjustable suspension that feels right, and a steel swingarm not prone to cracking.

The 900 CR looks friendly and sinister at the same time, like a comic book version of a snub-nose revolver. The shape is hard to capture in photos. In person, a 900 CR would remind you of Dreadful Flying Glove from the movie Yellow Submarine, except it’s red. By comparison, modern Ducatis look like cats.

The best part of riding the Ducati is how it demands your undivided attention, always, right now. The worst part is that it eventually runs out of gas, or the sun goes down. Then, the next morning, all other bikes feel springy, slow, and sad.

Tuning an old Ducati is a group effort

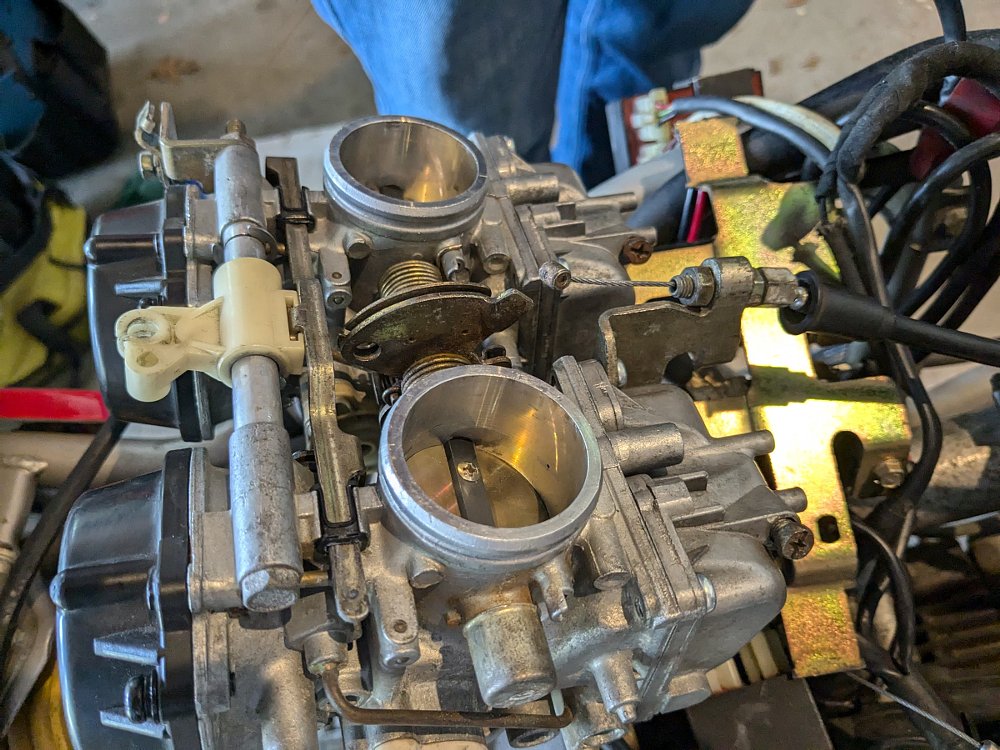

At first, the Ducati did not want to idle, although it was happy to hop on the main jets and bore a hole through its immediate surroundings. All signs pointed to the 38 mm Mikunis. Good news, rebuild kits are still available (with stickers!). That usually goes smoothly, because my son Leo shows up and meticulously follows every step, one tiny part at a time. This time was different. He’d brought home his girlfriend, all the way from California, and might have been a little distracted. We wound up with some partial carbs and some carb parts.

No matter. Keeping the old bikes around is as much about having an excuse to get together as actually getting things working. Over the next few weeks, a couple of friends and I puzzled over the carbs and scoured the planet for other parts. Some guy in Australia mailed us new idle jets. Somebody else found some brake pins and springs from a location unknown. I got new airbox clips direct from Italy, in plastic bags that had been hand-labeled when Bill Clinton was president. Brake pads come from Omaha. Every missing piece was a reason to hang out with the friend who sold me the bike.

To be honest, I don’t think he actually sold me the bike. My hope is that I am keeping it safe until he’s ready to ride again.

Until then, we let the old bike reveal its history as we worked on it. The front brake and clutch fluid look to have been flushed once a month. The back brake hadn’t been touched, hydraulics filled with liquid tar. Cam belts, new; tires, old. High-explosive lithium ion battery with unshielded wires nestled just beneath fuel lines; needs attention. One fried igniter; generic part from eBay works fine; order spares. The bike makes you think you’re a race mechanic. Pop the tank onto its little kickstand and everything’s right there.

Once you’re under the tank you start to notice that Cagiva, which owned Ducati at the time, left little elephant symbols here and there. Best part: You are assumed to know how to adjust desmodromic valves, but alongside the oil filter the word “filter” is cast in aluminum, in English, in case the spin-on filter itself didn’t tip you off.

When you take a thing apart and put it back together, you gain a special appreciation for how it was designed. In the case of the 900 CR, someone oriented the engine and wheels in space, then told a talented welder to connect everything with the minimum set of straight tubes in time for tomorrow’s track session. Toss in a headlight from an old Fiat, in the name of being street-legal, and it all winds up looking exactly right.

The result is a happy hot-rod with not one extra bit of anything. No liquid cooling, no fuel injection, the good half of the fairing. The oil cooler hangs down like a chin spoiler. It’s exactly what you need to sprint to the next curve and nothing else. I removed the passenger pegs, out of respect. Burn two gallons of gas tuning the idle, then your 900 is ready to ride.

Riding my 30-year-old 900 CR

First myth to dispel: sport bikes are spooky. The Ducati feels long and graceful. Despite some forward lean, it’s comfortable for hours. It handles with precision — feels like the front tire is in your hands — but it never twitches. There’s no lethal secret hiding inside.

The engine reminds me, again, that nothing feels like a big 90-degree twin except a big 90-degree twin. In this case, no fussy microprocessor tries to map every detail of the fueling, so the bike won’t snatch or lurch. Keep the revs over 4,500 and the Ducati howls on the cams and flies down the road, with torque everywhere. Roll on the throttle on a long uphill and it feels like the bike is rotating the planet beneath you. The brakes shed speed however you want. The exhaust makes a sound like the world is ending, in a good way.

I thought that riding it might be scary, but it feels completely natural. You steer with your whole body, by looking ahead to the next curve, moving around just off the seat, putting pressure on the footpegs along with the hand grips. At first I held the tank and bars and stayed inside the bike, then I loosened up and hovered over the bike, letting it float beneath me. I just point my helmet and the chassis follows, steady when leaned over. It combines high stability and low weight, encouraging you to get comfortable, then to start tossing it around.

Parking lot maneuvers, however, are not recommended.

Back in 1995, Ducati made a bike that is violent and gentle at the same time. Don’t get me wrong, it’s fast — making my Triumph Tiger 900 feel like a rented Corolla — but never getting away from you. Every transition is smooth, once the engine is spinning. Every ride is a regular ride, apart from the future arriving ahead of schedule. The biggest surprise is not feeling beaten up. Someone built this bike for the pure joy of blasting around, then being ready to go again tomorrow.

Spending the summer with the bike led to lots of debate. Was 1995 peak motorcycle, or at least peak Ducati? Nothing about the 900 CR seems like a luxury product or a lifestyle accessory. It’s a workshop special, plain and simple. These bikes sell for $5,000, even when one of your best friends isn’t giving you an inside deal. Getting them squared away takes another $1,000, some spare time, and a sense of humor. That’s a little more money than a Kawasaki Ninja 500, for something you can park in your living room over the winter, as a piece of sculpture. Bear in mind: Maintenance is a part-time job. Getting the bike set up at a Ducati dealer might have cost about what I paid for it.

My friends and I have another project. We are building a barn on a hillside in southern Vermont, half machine shop and half camp, with long porches and a hot shower. All the bikes will live there, once it’s done. The dream is to have a place to keep the tools organized and make coffee. The same crew that works on the bikes is working on the barn. They are in charge of construction. I buy cookies and help out where I can.

I think that’s the point of keeping the older bikes going. It doesn’t cost much, it’s incredibly rewarding when you’re out riding, but mostly it’s a group effort. The barn will feature two Honda CB500s from the early 1970s, a Honda XL350R from 1985 that really could use a piston, a Royal Enfield Hunter 350 as a pit bike, and whatever else wanders in. There’s a BSA rumor but it’s unconfirmed. The Ducati is the star of the show.

Read More

Top Five Most Common Questions About Car Fuel Averages

The Future of Classic Cars: Electric Conversions and Modern Upgrades